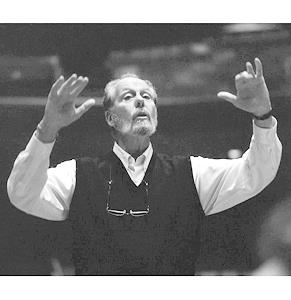

George Corwin

My first communication with George Corwin must have been around 1994. I had reviewed a performance he had directed, with the UVic Chorus and Orchestra, of Sergei Prokofiev's cantata Alexander Nevsky, one of my favourite pieces, and was overwhelmed. But, at a time when I was still finding my way as a critic, I clearly felt the need to say something critical and so questioned a few of his tempos.

In a remarkably polite letter, George informed me that he was simply obeying the composer's instructions in the score.

This, of course, was one of George's great strengths, his ability to direct the score precisely as written while still giving a performance of stature and individuality: something of which many conductors seem constitutionally incapable.

Over the years I got to know George quite well, for which I shall be forever grateful, and realised that for him, the music was everything. And while I am certain that he possessed as much ego as the rest of us, he never once, in my experience, imposed himself on the music, having clearly taken to heart the remark made to him by Igor Stravinsky that "your job as a conductor is not to interpret the composer's music. It is your job to find the composer in his music and allow him to speak". (Moreover, in none of the numerous conversation we had together did he ever begin a sentence with "As Stravinsky once remarked to me...")

I cannot speak, other than by hearsay, of George's career prior to my first hearing him conduct, but I did enjoy hearing from his own lips his account of his time in New York as one of several protegés of Leonard Bernstein and also of his being invited to join the staff of the famous Eastman School in Rochester, NY, by the legendary Howard Hanson and of assisting him to correct the "hundreds of mistakes" in the printed score of a work we both adored: Percy Grainger's A Lincolnshire Posy.

Indeed, I believe one of our first meetings was when he very generously allowed me to attend the dress rehearsal of his final concert with the UVic Wind Symphony (a prior commitment kept me from the concert itself) at which the Grainger was being performed.

Over the years I attended many concerts directed by George, notably his decade-long stint with the Civic Orchestra, whose playing standards improved almost beyond recognition during that time. A year or two (perhaps more) before he finally resigned from that post he asked the orchestra (who then asked me to assist) to judge whether he was still up to the task or whether he should quit while he was still ahead. My immediate response to the orchestra's committee was that of course he should continue.

Eventually, of course, he decided that it was time to go, but not time to retire.

But first he closed his time with the Civic with a farewell concert whose programme maintained his tradition of treading the road "less travelled by": Bernstein's overture to Candide, Glazunov's Sixth Symphony and Berlioz's song-cycle Les Nuits d'Été in which the superb soloist was his granddaughter, Charlotte.

After his departure from the Civic, George certainly kept himself busy and not necessarily in precisely the manner one might have expected.

Who would have guessed, for example (certainly not I), that George was a big Gilbert and Sullivan enthusiast? His work with the Victoria G&S Society is the stuff of legend and he reinforced my own enthusiasm for the Savoy Operas, with a number of productions, in both staged and concert performances. Perhaps the highlights were the two performances of The Mikado — one in concert with accompaniment by the Civic, the other staged and accompanied by a carefully chosen chamber ensemble. The Mikado was also truly a family affair: in addition to his wife Joanne singing in the chorus and his daughter Jennifer portraying one of the Three Little Maids, his son Lucas gave one of the finest, funniest Ko-Kos I have ever witnessed.

But George would also pop up with yet another self-created ensemble: his sadly short-lived Concentus Corwinus — who gave a superb performance of Stravinsky's L'Histoire du Soldat (in, of all unlikely places, a hotel in James Bay) — and the Ensemble Pacifica, a hand-picked wind band, were prime examples. And, as was his apparent predilection, the ensemble's repertoire was as far from the beaten track as one could wish: for example, Enescu's Dixtuor — a work I had scarcely even heard of, much less actually heard — or the Harmonie arrangement of Beethoven's Seventh — something I had been wanting to hear in the flesh for at least two decades — or Hummel's music for the fairy-tale Die Eselshaut (The Donkey's Skin). And even their more "conventional" programming, such as Gounod's Petite Symphonie or Richard Strauss's Serenade for Wind Instruments, was hardly commonplace.

But I imagine that for George, the most fulfilling of all Ensemble Pacifica's concert was that in May 2012, in which he fulfilled an ambition he had nursed for some forty-five years and finally conducted a (needless-to-say superb) performance of Kurt Weill's Concert For Violin and Winds, having found in Pablo Diemecke a soloist both capable and willing to take on the task.

Looking back through my archives, I find that I do not have as many reviews of George's concerts as I had imagined, which, to me, signifies what a long shadow his performances cast: their significance and memorability far outweighed their frequency.

As mentioned above, George was one of those rare musicians who can take the composer at their word — by which I mean he would meticulously follow the directions in the score — and yet unfailingly produce a performance which, while blessedly free of any signs of egomania, nevertheless gripped one's attention throughout and was as far from the bland as one could imagine.

This was, of course, particularly noticeable in his performances of the standard repertoire. But his music-making was by no means limited to the familiar; indeed I am endebted to him for introducing me to much terra previously incognita.

In some cases — as with the Hummel, the Enescu or the Weill — the music was scarcely recent, but seldom performed. In other cases it was brand-new, such as the memorable 2007-8 season with the Civic Orchestra in which every concert contained a world premiere. I can imagine few, if any other community orchestras having the temerity even to attempt such a feat. In George's more-than-capable hands they succeeded beyond all reasonable expectations.

I shall forever regret that somehow I managed not to catch his last public appearance, with Deimecke's DieMahler Ensemble, in which he directed both L'Histoire du Soldat and Walton's Façade, with the participation of three of his children: Jennifer, Lucas and Todd.

But I shall also forever thank my lucky stars that I got to know this great musician as well as I did and for all the wonderful performances I did manage to attend.

With George's passing a Golden Age of orchestral conducting in Victoria finally came to an end.