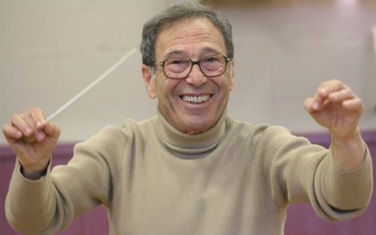

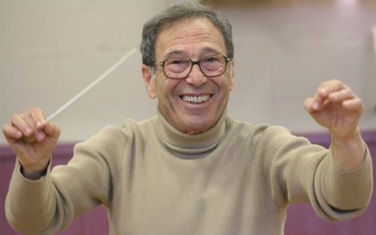

János Sándor

János Sándor, who died on May 14, was one of the most remarkable people I have ever met. A great musician, to be sure, but also a wonderful human being, who inspired his musicians to heights they were probably unaware they were capable of.

Of János's career before he and his family arrived in Victoria, I cannot write from firsthand experience. His achievements since arriving here are entirely another matter.

I believe I first heard János conduct in the summer of 1996, in Christ Church Cathedral. The old Victoria International Festival had collapsed after the previous summer and there was undoubtedly a gap to be filled. The Victoria Symphony rapidly put together a short season of orchestral performances most, if not all of which were conducted by János.

My abiding memory of this season is a performance of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony in which the notoriously resonant cathedral acoustic was tamed as I have rarely heard it before or since.

Why János never again conducted the Symphony is, to me, a continuing mystery.

It did, however, leave him free to stamp his mark, indelibly, upon the musical life of this town: as conductor and trainer of the University of Victoria Chorus and Orchestra, and the Greater Victoria Youth Orchestra. (Nor should one forget his year with the Civic Orchestra of Victoria, a year of greatly improved playing standards.)

As one who has been regularly attending the concerts of both University and Youth orchestras, I can testify to the gradual and inexorably rise in quality of both; although I am sure that János, always one of the most modest of men, would have happily ascribed this to his musicians' teachers and trainers, I remain in no doubt that János's own personal qualities must be accounted the major factor.

I can still clearly recall attending a final rehearsal for one of his UVic concerts - probably around 1999 - and witnessing him spend several minutes repeating the same few bars of Rossini's William Tell overture until the timpanist got the hairpin dynamics exactly to his liking.

Yet this was done in the gentlest possible fashion and it was clear that the timpanist's only wish was to "get it right" for him. (And, of course, János began his own professional career as a timpanist, so knew precisely what he wanted and how to achieve it.)

On another occasion, while chatting with a member of the UVic chorus, I was told that during rehearsals he would sometimes appear to become annoyed when the musicians persistently made mistakes, but that he was unable to keep up this stern attitude and would usually end up laughing, in spite of himself.

And yet - in sharp contradistinction to the convention wisdom that to be effective a conductor must be barely recognisable as a human being - this jovial, gentle man nonetheless left a legacy of memorable, even great performances.

Perhaps the most memorable of all was just over a decade ago, as his two orchestras joined forces to celebrate the millenium with the first-ever Victoria performances of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No.8, the so-called "Symphony of a Thousand".

Some months before the performances, János contacted me and asked if we could have lunch together; I have something of a reputation (thoroughly undeserved) as a Mahler specialist and he wanted to pick my brains.

In the event, all I was able to contribute were a few remarks about the physical staging of the work, based upon the performances I had witnessed.

The ultimate success of the concerts was 100 per cent János, whose innate musical taste and sense, and unfailing sense of the "long line" resulted in two performances of real stature; a remarkable achievement in any circumstance, but one which, given that (as far as I am aware) neither he nor anybody else on the stage that weekend in April 2000 had ever performed the music before, confounded all reasonable expectation.

If I may employ a sporting metaphor (moreover, a sport which neither János nor I grew up with), it was as if he had stepped up to the plate and hit the first pitch right out of the park.

János was a representative of the great Central European musical tradition and brought a particular authority to his performances of the central repertoire - music which he was eager to expose his young musicians to, especially those contemplating a career in music.

It was hardly unexpected, then, that his Beethoven, his Brahms, his Tchaikovsky, his Wagner were all something special. And, of course, his Bartök and Kodály were sans pareil. But how, then, can one explain his thoroughly idiomatic and deeply moving performances of Elgar's "Enigma" Variations and Vaughan Williams's Sea Symphony, except by referencing his innate musicianship and devotion to the score?

His "stick technique" was fabulously expressive and elegant, yet he never over-conducted and knew exactly when to let his musicians have their head - as witness that wonderful moment in the GVYO's Twentieth Anniversary concert when, at the climax of the last dance from de Falla's Three-cornered Hast, he simply stood, arms open wide, his baton barely twitching.

Moreover, at an age when many musicians are happy to stick with the music they know and love, János was always open to new music - I would regularly run into him at concerts by the UVic Sonic Lab (which he even conducted on one occasion) and Aventa. I even once bumped into him at a concert given by the Palm Court Orchestra (his wife, Maria, was playing in the first violins). "You know", he said to me, "we have nothing like this in Hungary - it is wonderful!".

And his sense of adventure also made him most receptive to suggestions, even from a humble amateur such as myself. I shall forever be endebted to János for performing Sibelius's Symphony No.2 with the Koussevitsky-emended timpani parts in the finale, and Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique with the all-too-rarely heard cornet part.

I must mention his other musical legacy, his musical "heir" Yariv Aloni, who turned to János for instruction when he first picked up a baton and who has worked side-by-side with him at the GVYO for years. János was nearly always present when Yariv conducted and I can clearly recall seeing him, just over a year ago, when Yariv conducted the Galiano Ensemble in an all-English programme. "You must be very proud of him" I said to János. "Oh yes, I am!" he said, beaming.

János bore his final illness stoically and I would venture to suggest that few of his young musicians realised just how sick he was. I believe that, during the last months, it was sheer will power that kept him alive - and, of course, his love of music. After his penultimate concert back in March I was talking with his wife, Maria, who told me that he would frequently tell her that he was going for a rest, yet a little while later she would find him with his head buried in a score.

I must now, regretfully, accept that I am never going to hear János conducting more Mahler or Bruckner, that I am never (perhaps saddest of all) going to hear him conduct Liszt's "Faust" Symphony.

But that knowledge is more than compensated for by the memories of all the extraordinary performances I did hear him conduct.

On the afternoon of János's death, I listened to the first part of the recording of that millenium Mahler 8. Although this is music I love, it does not usually move me to tears.

On this occasion, it did.

János is gone and he will be greatly missed, but in his fifteen years in Victoria he enriched the lives of all of us who knew him, or heard him conduct.